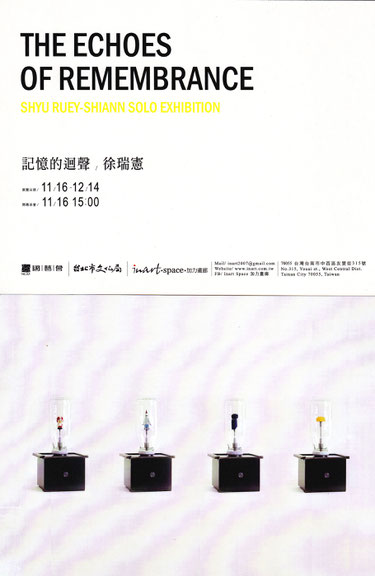

The Echoes of Remembrance: Shyu RueyShiann Solo Exhibition

2013/11/16-2013/12/14

Inart Space, Tainan

「記憶」乘載著人一生的活動、感受及經驗的印象累積。在某個時刻、某種氛圍、味道、聲音或某首旋律的催化提示下,腦中自然浮現與之相連的片段記憶,或許令人感傷,也或許令人歡欣,總是不知以何種形式、無預警的直搗靈魂的核心,重拾我們以為已遺忘的過往或瓦解我們層層建立的防禦機制。一旦牽動了那細微的感知神經,我們的靈魂彷彿瞬間滑入過去的時空隧道,同時遊走於過去、現在、未來的時空之中。

「記憶」於徐瑞憲而言就像是生命中忽隱忽現的迴聲,也是其創作的主軸與靈感來源,在一堆承載著歷史記憶的回收舊物件及冰冷的零件、馬達、齒輪等金屬原料之中,創造出全然失去時間感的浪漫片刻,他為作品注入豐富又穠纖合度的感性詩意,撩起觀者靈魂深處那既深沉又單純的回憶,細緻輕盈的誘發出你我情緒反應,使內在情感與深層記憶得以浮出表面,或悲或喜!殊不知背後那複雜精良的設計與製作是藝術家燃燒自我生命的熱度,以極度勞動性的方式所完成的。

近二十年持續不斷的創作與對材質探究的堅持,以及對過往、童年記憶的頻頻回盼,一則出自徐瑞憲個人私密情感的投射,一則是對現下社會環境包括人與人、人與自然及人與物件和空間的反思。在城市現代化的過程中,我們常常無感的以摧毀的方式來面對具有豐富生命故事的老物件,生活中所有的景、物,漸漸地失去了溫度,徐瑞憲將具有時間性的味道融入作品之中,當作品啟動運轉時,物件中具有獨特的味道亦同時散發出來,以無形的感官知覺,呈現出一種近似消失的生命記憶。

美國藝評家Richard Vine曾提到,當我們在看徐瑞憲的創作生命時,必須謹記T.S. 艾略特的「非個性化」的詩歌理論,艾略特認為真正的藝術所呈現的方式並不是人格的直接表現,而是對媒材徹底、精練的實踐。「詩不是情感鬆散的轉向,而是情感的出口」,據此,對徐瑞憲而言,藝術創作是一種尋覓出口的方式,亦是一種昇華!對家人情感如此,對人與自然、環境變遷的反思亦是如此。

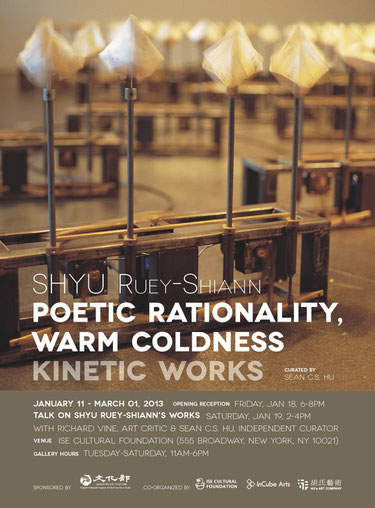

Poetic Rationality, Warm Coldness: Shyu RueyShiann Solo Exhibition

2013/01/11-2013/03/01

ISE Cultural Foundation, New York

Poetic Rationality, Warm Coldness is an exhibition of three kinetic artworks created in different stages of time by Taiwanese artist, SHYU Ruey Shiann, and they are Life and Death, River of Childhood, and Trace. Through the exhibition, an opportunity is presented to the audience to understand the artist’s creative context and concepts and to get a glimpse of his internal world and his dynamic creative aesthetics.

SHYU is known for his art created with mechanical elements. He uses his hands to turn complex mechanical concepts and installations into simple and concise artistic expressions, as cold hard industrial materials are transformed into abstract and warm three-dimensional sculptures. Binary contrasting relationships, such as rigid/soft, cold/warm, rational/emotional, give SHYU’s art a dynamic and conflicting power that is also touching and poetic at the same time.

The artworks included in this exhibition distinctively represent the artist’s concerns for the nature and our environment and also his nostalgic recollections of childhood memories. With the machines’ slow movements, the artworks resemble old gramophones or time machines that are able to transport us back to beautiful times in the past, as a sense of resonance echoes in life’s shared experiences. Life and Death is the first artwork the audience encounters at the exhibition, and with this simple installation, the artist intends to express the idea that all living beings on Earth are equal and human behaviors have caused drastic ecological changes; before the extinction of more life, please protect and respect the world we all live in. The second artwork, River of Childhood, is an installation of small boats. The electric current guides the audience on an expedition back in time to search for nostalgic memories. While reminiscing the changing sceneries before us, we are prompted to question whether the progression of time has taken away our original hopes and dreams? With the last artwork, Trace, the moving charcoals of the piece appear to be dancing and swinging, and with each stroke and line, traces are left behind as marks of time. Just as time has also inadvertently left its traces in life, from which, an internal landscape of the self is thereby formed.

SHYU Ruey Shiann is one of the important pioneers in Taiwan’s contemporary kinetic art. He uses machines to express emotional burdens and little by little recounts reflections he has for life and nature, as new significance is given to the medium of metal. SHYU gained recognition from the art world in France during the time he spent there in the 90’s. In 1997, he was the first place recipient of the French National Senior Diploma in plastic expressions. In the recent years, he is frequently invited to participate in international exhibitions, including Kinetica Art Fair in Ambika, London, Lunarfest in Harbour Front Centre, Toronto, and Tenri Cultural Institute, New York. In 2012, SHYU was invited to present his solo exhibition, Distant Rainbow, at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, which received many positive critical reviews.

*************************************************************

*************************************************************

The Coping Mechanisms of Ruey Shiann Shyu

Eric Shiner

Ruey Shiann Shyu is a master of making the otherwise hard materials of industry and work into elegantly flowing and poetic assemblages that twist, turn, undulate and flow

in incredibly alluring and thought-provoking ways. This is no small feat for an artist who chooses to work in machinery, the type of equipment used to fuel engines, generators, and in essence our

daily lives. His sculptures seem to strip away the outer shells and frames of commercial materials to expose their inner workings, and yet, each of his works becomes a fully self-reliant system

of signs and systems that play on shared notions of history, memory and sentimentality. Through harnessing energy and presenting it in the form of simple gestures and movements, Shyu's works take

us into a nostalgic realm where dreams and memories collide in often times surprising ways.

I have always been impressed by Shyu's ability to create sculptures that seemingly dance in an effortless yet fully choreographed system of movements that rely on direct or kinetic energy to

function. Whether it be a drawing machine that continually lays graphite on the gallery wall or a gallery full of ceramic origami boats seemingly riding invisible waves, Shyu is able to create

purely timeless, and I dare say, romantic moments amidst the gears, cords and engines of his hand-made machines. He brings an incredibly skilled sensibility to his craft, and instead of creating

bulky robots or churning monsters, he instead deftly produces delicate armatures and systems that work in complete harmony, so much so that the engineering of his complex systems is happily

overshadowed by the narrative of magic that unfolds through each work's actions. It might be said then that Shyu becomes not a mechanical engineer, but more accurately a social engineer who

elicits our emotional response as we encounter his most conceptual contraptions.

This relies on a very well developed notion of play, as though both the artist and audience share in fond recollections of childhood playtime, where the worries of the world fully disappear as we

remember our own toys from our youth. Shyu takes the basic underpinnings of our Erector sets, model kits and remote-controlled cars and re-imagines them as fully adult systems of art production.

He makes these otherwise simple implements of play into fully theoretical vehicles that deliver deep-seeded human emotion through mechanical motion, and in so doing, taps directly into the human

psyche. And in so doing, and in much the same way as he exposes the inner workings of his sculptures, so too does he lay bare our mind sets and memories, allowing us to become fully absorbed in

his swaying pieces with the same attentive awe that we encountered as children when faced with the newest gadget or gizmo.

Of course, when one chooses to mine our shared childhood memories, it is necessary to realize that both trauma and pleasure will rise to the surface. All of us have encountered both poles in our

youth across a sliding scale of impact and force. The various traumas that we encountered were in many ways subsumed or masked by our imaginations, in that we no doubt created a system of coping,

relegating these things into our subconscious. Conversely, we also remember--and more readily--the joyous moments of our youth, the so-called good times where laughter and unfettered pleasure

reigned supreme. These memories also rely fully on our imaginations, in that we no doubt constructed fantasy worlds populated by princesses, dragons and rainbows to either escape from reality, or

perhaps to prolong our innate happiness. No matter where one falls on the spectrum between the overarching prevalence of happy versus traumatic memories, there forever exist certain catalysts and

prompts that unexpectedly trigger our memories, sometimes resulting in sudden and unprovoked tears, smiles, or sometimes both. These triggers somehow go straight to the core of our psyches, fully

avoiding the many layers of baggage and coping mechanisms that we have constructed to keep them at bay. We never know what these agents might be, what form they will take, or how we will respond,

but when we experience them and the resultant visceral reactions that come with them, we know that the prompt has revealed a memory of import to us.

In thinking of this, It becomes apparent that Shyu is very consciously creating mechanisms that strive to do this very thing. Through their motions and constructs, they attempt to strike at our

inner core, and in so doing become seductive traps that might very well provoke a strong, emotional response from the viewer. These responses will invariably range from the warm memories of

constructing a toy kit with one's parent to something much more sinister in the form of an accident or injury at the hands of a machine, automobile or electronic device. These are experiences we

have all shared, and Shyu very slyly taps into this most important relationship between humanity and technology. In our modern age, the gap between these two poles draws forever closer, seemingly

on course for the two to fuse fully and finally in the not-so-distant future. Shyu realizes this, and as such, his work becomes even more poignant and timely as a result.

In closing, we might then say that Ruey Shiann Shyu is a mediator between the realms of humanity and technology. His artworks might be viewed as his tools of evoking emotional response, just as

they can be read as the vehicle through which he links memory and the here and now. Through his constantly rhythmic constructs, he makes us feel at ease, allowing our inner feelings and

deep-seeded memories to rise to the surface. What we opt to do with them once they arise is up to us, just as we won't know if the memory will be a fond or sad one until it appears. No matter the

end result, we can definitely look to Shyu's incredibly powerful and sublime sculptures and installations to act as the catalyst that can deliver us to the very core of who we are, and more

importantly, to expose the reasons behind why we are the way we are. And just like his bare wires, revolving gears and skeletal armatures, so too do we stand fully exposed when in front of his

timelessly poetic work.

Eric Shiner is the director of The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, PA, USA

***********************************************

***********************************************

Paradoxes of the Wheel

Maud Jacquin

When I first met Shyu Ruey-Shiann in his New York studio, he emphasized the significance of an early kinetic work entitled Writer’s Vessel (1997): a bicycle wheel laid flat on a large steel plate, with white feathers placed at the extremities of its spokes. When it comes to life, the wheel starts its slow drift on the floor while the spokes gently extend and contract, animating the feathers with a graceful movement. Shyu didn’t explain to me just why this work meant so much to him. But it elegantly condenses many of the ideas, emotions and tensions that traverse his oeuvre, offering an ideal point of entry into his poetic universe.

When seen as quills or ‘writer’s vessels’, the feathers tell of Shyu’s admiration for French classical culture and of his art education in Aix-en-Provence, an experience that had a lasting impact on his practice (it is in France that he began experimenting with mechanical sculptures). Because he picked them up on the streets throughout his stay in France, the feathers also evoke his obsession for collecting anything and everything, as well as his habit of creating his work from accumulated everyday material, both physical objects (feathers but also train tickets, motors or discarded mechanical parts) and personal memories.

More importantly perhaps, Writer’s Vessel reveals the dualities that inform Shyu’s entire body of work. Whereas the wheel, the motor and the cold steel plate conjure up ideas of technology, mechanical precision and control, the feathers evoke the instability and fragility of life and, in relation to the quill pen, symbolize the power of the imagination. The movement itself has a sensual quality, one that recalls the oscillating motion of leaves in the wind. Here, the machine becomes the agent of apparently unpredictable and organic rhythms.

This juxtaposition of the mechanical and the living, the solid and the fragile, the permanent and the ephemeral recurs frequently in Shyu’s practice. As in The River of Childhood (1999) in which sturdy metal constructions are crowned by delicate ceramic boats, or in more recent pieces such as Mom’s Drawer (2011) or The Edge of Memory (2012) that combine bulky physical objects with projections of fleeting images, Shyu’s kinetic works almost always imbue the strength and dynamism of the machine with fragile materials and evanescent subject matter, often inspired by the artist’s own childhood memories.

The wheel itself embodies contradictory meanings that often co-exist in Shyu’s art. Because its invention constituted a major technological advance that coincided with the beginnings of civilization, the wheel often signifies human progress and growth. Its association with motion and transport reinforces the symbolism of linear time and continuous progression (the journey is a recurrent theme in Shyu Ruey-Shiann’s work and was even the title of one of his exhibitions). In Western art history, the Bicycle Wheel (1913) marked another beginning: Marcel Duchamp’s first readymade is often considered to be the first kinetic sculpture. Yet at the same time the wheel is also connected to circularity and return; and the circle is a motif that constantly reappears in Shyu’s work, either literally as in Pregnancy (1999) or Shadow’s Journey (2011) or as an organizing principle in works that explore ideas of repetition and pattern such as One Kind of Behavior (2000) or the aptly named Recurrence (2000).

According to Taiwanese critic Chia Chi Jason Wang, the theme of the circle is key to Shyu’s work and the psychological processes that inform it. “[The circle] is an embodiment of the continuous search for self-fulfillment and completion with imperfection,” he writes.[1] Shyu’s persistent return to circular movement can also be interpreted in relation to more abstract cosmological and metaphysical considerations. In 2000, the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) hosted an exhibition entitled ‘Forces Fields: Phases of the Kinetic’, which traced the little-known history of kinetic art in an extended sense - i.e. an art that “reveals space, time and energy” – showing works by Gabo, Moholy-Nagy, Calder, Tinguely and Medalla among many others.[2] The main conceptual thread of this exhibition concerned the fascinating connection that exists between experimentation in kinetic art and what curator Guy Brett called ‘cosmic speculation.’ Indeed, for many artists included in ‘Force Fields’, material and formal exploration is tied with a reflection on the nature and structure of the universe.

Shyu’s work undoubtedly participates in this tradition of kinetic art as cosmological investigation. The titles of his sculptures and installations speak for themselves: some explicitly refer to the scientific rules that govern the universe - Newton’s Tree (1997), The Law of Relativity (1999) or Gravity (2003) – while others demonstrate a broader interest in metaphysical concerns – Life and Death (1995), Time and Being (2011) or The Beginning, The End (2011). And because his vision of the world is anchored in his own Taiwanese culture, it is no surprise that the circle returns as a leitmotif in his art. In Chinese philosophy, which is rooted in the “three teachings” of Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism, the emphasis is placed on the cyclical aspect of life and cosmos and on the acceptance of the ephemerality of all things. In Taoism, for instance, the universe is the visible manifestation of ‘Qi’ - the vital energy that is the source of all experiences – and as such, it is involved in a constant process of transformation and re-creation.

Shyu’s Eight Drunken Immortals from 1997 evokes this tradition not only in its title – the Eight Immortals are mythological figures revered by the Taoists – but also in its reference to activities involving the control and manipulation of Qi such as Kung Fu or calligraphy. But it is a later work called The Beginning.The End (2011) that offers the most immediate expression of the artist’s metaphysical vision. A plumb-bob (a small metal weight used by engineers to create vertical lines) is suspended from the ceiling. Aligned on the same vertical axis is a steel bar placed on an iron pipe fixed to the floor. The plumb-bob and the bar move up and down together in a regular rhythm, always leaving the same empty space between them. For Shyu, this sculpture explores the concept of emptiness that is so central to Eastern philosophy (and to traditional Chinese painting) and gives tangible form to the perpetual movement of transformation and renewal that govern the world and the individuals within it. Indeed, it was inspired by a poem by Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei, which offered a metaphor of the cyclical nature of life.

In this context, the wheel in Writer’s Vessel carries a metaphysical symbolism that relate to an Eastern, circular conception of life and being. This is all the more true since the wheel itself is an important symbol of life and time in Buddhist iconography, one that appears on countless temples in Asia. For Shyu, the feathers also represent life, its beauty and fragility. When he finds them along his way, he has said, “it is as if the gods had given [him] the present of a life … all of them are different and unique.”[3]

Like Writer’s Vessel, the works shown in Shyu Ruey-Shiann’s exhibition at the ISE Cultural Foundation in New York tell of the impermanence and fragility of life. Composed of dozens of delicate ceramic boats condemned to repeat the same arrested movement, The River of Childhood expresses the ungraspability of the past and conveys the artist’s nostalgia for a simpler time when children could create worlds of imagination from almost nothing. The other work, entitled Life and Death, is an egg box made of concrete with only one ‘real’ egg in which was placed a light source that pulsates at a frequency similar to heartbeat. When spectators approach, the light flickers, threatening to disappear.

Together, these pieces reflect another of Shyu’s preoccupations: the ecological threats posed by today’s frenzied race toward ever more production and consumption. His concern for life is not just a personal or a metaphysical concern; it is also a political one. “All my works deal with environmental issues in one way or another,” the artist explains. “I want my work to effect change. I believe in progress and in the power of science to effect change. In that sense, I am closer to Western culture.”[4]

Shyu Ruey-Shiann’s work is rooted in an Eastern philosophical tradition that conceives of the world as a living organism - with all the instability and unpredictability inherent in living systems - whose harmony must not be disturbed. This conception entails a sensitive attention to nature but also an ethics of non-action (‘wu-wei’ or non-action is a fundamental concept in Taoism). On the other hand, Shyu embraces a Western notion of progress, one that implies a politics of intervention for better or for worse. Progress and renewal, forward motion and cyclical motion: we are back to the paradoxes of the wheel. The wheel, it turns out, does not only reflect the productive encounter between two systems of thought. More than that, it serves as a metaphor for Shyu’s political and ecological perseverance: progress and preservation are the same enterprise, and if the aim is progress and change, the only method is to circle again and again.

[1] Chia Chi Jason Wang, ‘An Open Circle and the Memory Loop – On the Aesthetics of SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s Kinetic Sculptures’ in Distant Rainbow: SHYU Ruey Shiann. Solo Exhibition, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2012.

***********************************************

***********************************************

Poetic Rationality, Warm Coldness

Sean C.S. Hu

Poetic Rationality, Warm Coldness presented at the ISE Cultural Foundation in early 2013 was Shyu Ruey Shiann’s second solo exhibition since his relocation to New York. Three iconic kinetic artworks were selected from Shyu’s art career of two decades, and with an exceptionally succinct yet profound approach, these three artworks displayed three phases in the artist’ creative journey accompanied by three distinctive emotional states.

Shyu has long decided two decades ago that he would devote himself to kinetic art, which was quite a rare direction to take in the Taiwanese art setting at that time, especially with people’s pre-conceived notion that kinetic mechanical and technological art are often cold and aloof. However, on the contrary, through Shyu’s dedication and personal gestures, he has altered people’s doubts and questions about technological art’s much criticized or questioned aspects of rationality and coldness, and thus changed people’s stereotypical impressions. This is what Shyu is most renowned for and is what makes his art brilliant. Strictly speaking, taking meticulous attention in every detail of one’s artistic creative endeavor is not something out of the ordinary; however, to insist on personally cutting, molding, installing everything, the approach of taking everything into his own hands holds a very special significance to Shyu. Every medium and decision applied to his art, excluding motors, computers, wheels, wirings, and other readymade objects that he couldn’t personally make due to practicality, is created by the artist himself and made by his calloused and scarred hands from years of art-making. Perhaps some people may find his insistence hard to comprehend; since it is not uncommon practice to create art with purchased objects or to be installed by others. The reason behind his approach is because of his chosen way for conceptual production, which produces outcomes that are unique and irreplaceable. At the one hand, perhaps certain required parts he needs may not be available in the market, and on the other hand, for Shyu, the making of those parts and objects are synonymous to a painter’s brushstrokes and color choices on a canvas. Each gesture is representative of the artist’s dedication and artistic expression embodied by each of his artwork, and every creative endeavor is a new life’s exploration and experience.

Moreover, in each of Shuy’s installation pieces, the sense of rhythm and speed created seems to transform into exhaling and inhaling breathing rhythm in the exhibition space. The dynamic energy brings a surge of change in the ambiance, and each installation is a self-portrait of the artist transformed from his personal experiences, emotional extensions, or sometimes even catalyzed into the formation of some unknown beings. Related to Michel Foucault ‘s Technologies of the Self, Shuy applies his own self technology to bring impacts to his physical, spiritual, and mental behaviors, and which are transformed into his personalized tools. The result is that as the audience looks at his art, a strong intimate exchange is formed. A state of existence is extended from Shuy’s art, as the mechanical pieces are welded and composed meticulously into living breathing beings. As the purely materialistic and mechanical relationship is detached, a spiritual level is formed. In other words, Shuy’s art is comprised of the state of the “self” and the “physicality” from the material existence. The transcendence embodied by his art breaks free from the dichotomy between material substance and spirituality. As the material-based restrictions are broken, a new relationship is formed between people and the world, and due to the realm created where the material and the self are fused together, the art thus transcends beyond being robots or mechanical beings; they have evolved into creatures infused with life’s essence and emit a sense of vitality from within. Therefore, from Shuy’s art, we see a sense of warmth, poeticness, and reality, and his creative works have become an important pioneering indicator for technological art in Taiwanese art history. In the past decade, Taiwan’s art scene has paid focus to the trend of new media, with discussions on works that connect technology with non-technological elements and forms of kinetic and non-kinetic pieces, and from which, Shuy has become an artist of highly personalized style. His works emanate a classic essence while infused with technology, and amidst the classic elegance is an edgy technological style. His art is the combination of the new and the old, with kinetic forms fused with still concepts. Going from the internal to the external, the dynamism created allows his art to project a strong emotional output.

Poetic Rationality, Warm Coldness is an exhibition comprised of works that Shuy has created during three phases of his creative career, and are proposed based on the qualities and spatial links embodied by these particular pieces. These artworks also demonstrate the artist’s Zen-inspired concept as expressed by a well-known Chinese saying that describes the stages of knowledge discovery: “See a mountain as a mountain; see a mountain not as a mountain; see a mountain as a mountain again.” Shuy takes from his life’s experiences and transforms them into the soul of his art, with kinetic machines as the flesh and bone. This is the transformation of his art, a progression of knowledge forming, and furthermore, this is an evolution of life’s journey, and from which, we are able to witness the essence of his life dedicated to art.

The first piece on exhibit, Life and Death, was created when Shuy was studying abroad in France in 1995. The piece represents the time when he was transitioning from painting to mechanic kinetic art. In contrast to his later more complex and challenging pieces, Life and Death is not composed with many technological concepts or elements, besides of the lighting effects employed. However, the piece marks the important transitioning point for Shuy’s art and suggests that even with the artist’s later works (amidst the phenomenon with technological and new media art, Shuy’s technological art seems to carry a classic, low-tech, and nostalgic quality), technology has always been just a medium utilized to express his creative concepts, and not something pursued by the artist with a superficial agenda. His creative core is based on the completion and presentation of the concept and not about achievements of forms or techniques, and this is why Shuy’s art has not been criticized for lack of humanity, as technological art often does. Furthermore, he has gained an irreplaceable position in the history of technological art in Taiwan. From such a simplistic piece as Life and Death, we are able to see the artist’s care and concern for life and the natural environment. In the matrix installation, the egg that is surrounded by other twenty-nine cement eggs seems to breath with a flickering frequency, as the piece acts as a warning urging for more respect for life’s different beings, and is inspired by the artist’s longing for nature since childhood. The work is an expression that all things are created equal, and from which, Shuy demonstrates that the concern for humanity has always been embodied in his art.

The second piece, River of Childhood, was created in the late 90’s to early 2000, upon Shuy’s return to Taiwan from abroad. Forty pairs of ceramic origami-shaped boats are included in this installation, and the piece is derived from the artist’s imagination inspired by his childhood mathematics class. His childhood was a time with insufficient resources; however, it was a carefree time nonetheless. Grades in school did not affect his curiosity and interest for life. What’s remembered is the intimate connection he has with the streaming river in his modest hometown, and as these small boats float on the interwoven electrical wires extending to the ground from the forty metal platforms holding these boats, the wires then come to form a river of memory with recollections from his childhood. As the ceramic boats sway and tilt, the audience is brought back into times past. River of Childhood is a concentrated essence and retrospection of Shuy’s childhood memories intermixed with the world of the grown-ups. The piece guides us on a float down memory lane and brings back memories of the time when Taiwan’s political climate was about to be liberated and its economy about to take off. People were poor then but wonderful memories were formed in that innocent era. It was a time when life’s beauty and connection with nature were so easily accessible and achievable.

Trace was created in 2011 after Shuy relocated to New York in 2010. Albeit the challenges along his journey of art have not lessened with age, Shuy’s emotional state and artistic vernacular now demonstrate a well-rounded maturity and ease. Trace is a quintessential example of this change. Installed at the display window of ISE Foundation, two moving metal rods glide with grace and also project an interesting sense of humor, which attract the busy New Yorkers passing by to stop and observe. Two pencils attached to the rod randomly leave behind “traces” as the rods move, and the traces seem to form an image of New York’s graffiti-adorned streetscape expressed in black and white. Through the accumulation and progression of time, a poeticness and an easy-spirited attitude towards life is projected by the work, and which makes a strong contrast to the fast-paced city of New York. This artwork is derived from the artist’s own traces in life, and is also the footprints slowly left behind from his different life’s experiences and accumulations.

From French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological point of view, we could categorize Shuy’s art as a fusion of one’s psyche with material substance. The relationship formed is not an autonomous system; rather, it is a state of interactive co-existence. The art created from which further corresponds to Merleau-Ponty’s notion of “the three orders of existence”, which deals with the dialectical nature and synthesis of the three orders of the physical, vital, and human. Through labor and machinery, Shuy allows the body’s activities of perception to interact with the world under the existing structure, and at the same time highlight the significance of existence. This is why even though his artworks are composed with mechanical parts; however, through the artist’s physical inputs with his body and hands, the pieces are able to transform into living beings of flesh and blood made out of machines.

Poetic Rationality, Warm Coldness is the core concept of Shuy’s lifetime of artistic devotion. The media and forms of these artworks involve highly professional knowledge and skills of mechanical kinetics, which are rarely employed by other artists. In addition to the technical challenges, the harsh financial reality has always been a deterrent against Shuy’s artistic endeavors; however, Shuy has never used these obstacles as reasons to prevent him from making art. On the contrary, art-making is a form of self-healing for him, which allows him to connect with his internal state and be liberated from life’s impediments. In his years of dedication in perfecting his rational knowledge and skill, Shuy also puts forth great efforts in experiencing life. His art is born from his expertise with mechanical kinetics, observations of the surrounding and life’s experiences, and from which, a poetic rationality is formed from technology, and the cold machines are bestowed with a vital warmness. In the span of twenty years, Shuy’s creative vernacular, style, content and perception have altered and become more matured and complete due to the progression of life. From the three artworks included in this exhibition, we are able to witness the different phases in the artist’s creative career and experience his creative essence and concept. Without forcing grandiose justification or message in his art, Shuy prefers to present his own points of view on life, and prompts us to return to the self and reflect upon our own lives.

SHYU RUEY-SHIANN 徐瑞憲

SHYU RUEY-SHIANN 徐瑞憲