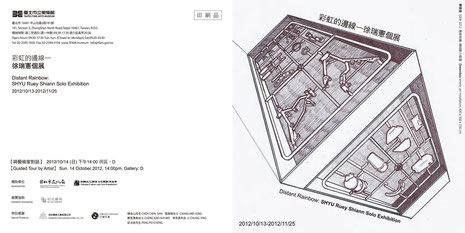

Distant Rainbow: Shyu RueyShiann Solo Exhibition

2012/10/13-2012/12/25

Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Artist SHYU Ruey Shiann’s creative form takes the shape of kinetic works. His understated individual aesthetic vision is expressed using the precision of kinetic theory, motors, gears and other mechanical parts. From conceptualization to realization, each of these installation works has gone through a process of experimentation, beginning with a hand-sketched mimetic diagram of the concept, to the deconstructed outline of its mechanical structure, a comprehensive installation plan, detailed description of the size of objects and their interconnectivity, and then the actual cutting and welding required for assembly – the entire production process requires detailed calculations and time-consuming adjustments.

SHYU Ruey Shiann’s work is a transformation of life experiences. His deep interest in kinetic art originates in his observations of life and of memory. The habit of collecting mechanical parts is a necessity of his art, or perhaps grew from his early childhood of helping his mother with recycling waste. The encouragement and early death of his older sister catalyzed SHYU’s self-funded study of Western sculpture and painting at the École supérieure d'art en Aix-en-Provence in France. The trembling lines and exaggerated composition of his oils during that time -- depicting views from his dormitory window, his wash basin and toilet -- reveal his sense of confusion and struggle while studying in a foreign country. With the encouragement he received in art school to use new media in his creations, he threw himself entirely and physically into his work, to the point where his instructors had to shut down the workshops to prevent him from being completely consumed by his work. His years of working with kinetic art installations have taken a toll on his health, and metallic dust has collected in his lungs. In a documentary of the artist directed by Huang Mingchuan, the closing shot reveal a close-up of the artist’s calloused fingers plucking at metal shavings; it is a poignant visual reminder of how art and life become one.

In this exhibition, the rainbow represents the ideals and dreams in our memory: pristine but ephemeral. The artist attempts to draw their outline from memory, to reveal a gradually forgotten or a vanishing dream. Upon entrance into the softly lit exhibition venue, four works sequentially call forth forgotten happy memories in an interactive way. In his work “The Edge of Memory,” a projector above casts a rectangular shadow on the ground that pendulums back and forth, to conjure a swing that is no longer present, but recalls the childhood laughter and feeling of flight while playing on a swing. In “Mom's Drawer,” based on the artist’s memories of his mother, an old drawer slowly extends out of a wall accompanied by the sound of a drawer being opened, and projects images toward the ceiling that fade then reappear. “Dreambox” is constructed using four large boards and motorcycle spare parts that are set into motion by a signal from the sensor, while the artist excitedly recounts his first motorcycle cross-island trek. “Afternoon Rhapsody” is performed by a primary school desk and chair which magically spin and dance around with the same endless energy and imagination of a child during school recess. The artist is attentive to the overall presentation of each vital individual work, enabling the works to narrate these stories and memories time and again.

In “Distant Rainbow”, SHYU Ruey Shiann uses shadows and sound to conjure idealized memories that seem just out of reach. He relies on many years of experience and intuition to transform and reorganize objects he has collected since childhood, blending new technology into old stories to create a subtle mix. Like a poetic rendition of waking from a dream, his kinetic art installation slowly reveals memories of childhood wishes.

***********************************************

***********************************************

An open circle and the memory loop

── on the aesthetics of SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s kinetic sculptures

By Chia Chi Jason WANG

If a “circle” represents a cycle without beginning or end, its repetition and reiterations unavoidably conjure associations of fate, predestination and even reincarnation. The rhythm and trajectory of circular movement has been at the core of SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s (1966- ) kinetic sculptures and installations since he first began presenting such work in 1997. From past to present, SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s creations have always been richly imbued with autobiographical characteristics. They hover over a world that is based on a personal history of growth. He seems indifferent to whether he has become obsessive, and never tires of using his works to describe his background. His expressions overflow with nostalgia. The memories of childhood are a main theme of concern in his work, and not only the happy memories. Within the innocence, there is also an undeniable purity. Or to put it another way, the happy innocence of childhood has become the singular creative loop for SHYU. It is a circle formed by habit, by rational conscious choice, by a subconscious emotional proclivity, or even by an unconscious psychological desire; it’s operations are governed by an unspoken rule.

In highlighting the innocence and perfection of childhood, SHYU actually represses and hides the numerous unhappy, imperfect or even regrettable memories in this process; at least, he selectively withholds and does not present these. In reality, SHYU’s upbringing was not particularly easy. He grew up in an impoverished lower middle class home. His father worked as a chauffeur for a wealthy family, while his mother contributed to the household income by scavenging. His older brother and sister dropped out of school at an early age to help bring in income. And domestic violence cast a constant shadow on home life. Even at an early age, SHYU exuded a sense of sorrow and grief. Even more intriguingly, when he came to kinetic art as an medium for artistic creativity, the circular rotation of a motor driven belt was actually a transformed representation of the “wheel”. Toward the end of his study in France in 1997, SHYU completed his Self Portrait ’96 which was composed of suspended wheels, large and small, in a complex interactive rotation that represented a portrait of an individual life state. The circular motion in Self Portrait 96’ easily conjures associations of SHYU’s father’s occupation as a driver for hire, or the silhouette of his mother’s scavenging cart; all of these pointing to life’s unavoidable and pervasive shadow cast by the “wheel of fate”. Worth mentioning too, is that even today, SHYU is still influenced by the virtues learned through his mother’s scavenging, and his works often reuse old mechanical parts that have been discarded and reclaimed. The circular motion of mechanical wheels that turn in SHYU’s works remain full of vigor and show no signs of giving in to the troubles of real life or resigning to fate.

Conversely, perhaps the imperfections of a family life that was constantly on the brink of fracture and crisis was the impetus behind the psychological compensative mechanism of the “circle” in SHYU’s creative process, representing a continuous search for self-fulfillment. Hence, the “circle” in SHYU’s work enables us to see the dual nature in real space-time: a seemingly powerless existence without an exit, in a daily repeating closed loop. The ceaseless longing and drive to achieve completion is a constant battle full of sound and fury. In his work, the rigid cold mechanical bodies emit heat and come to life through their constant motion. The kinetic rhythm renders order; the act of mechanical operation shapes the trajectory of that rhythm. This is SHYU’s personal mechanical waltz, highlighting the infinite and cycling nature of the circle, with both the fatalism of transmigration and the unstoppable power of rotation. It is an embodiment of a continuous search for self fulfillment and completion within imperfection.

An imperfect home life necessitated that SHYU find his own way out. Through the encouragement of his older brother and sister, he pursued his studies despite all of the hardships of youth, and threw himself into artistic creation and learning, which culminated in his going to France for further studies. This experience in self-fulfillment is expressed in his 1997 work, Self Portrait 96, a clear reproduction of the tortuous struggle and a tenuous terrifying balance. In the operational process where centrifugal and centripetal forces meet, leaving home was the first step toward SHYU’s pursuit of his dreams, and all of his endeavors went toward rounding out his personal goals. Symbols of life as “journey” often appear in his work. Using minimalist geometric designs, he created a mechanical model of migratory birds in flight. For instance, in his work Children of the Earth-Formosa (1998). Sometimes the wings of birds become actual tickets for passage, for instance, Traveler’s Wings (1998-2011), or in the 1999 work, The River of Childhood where SHYU uses collective motorized momentum to create a visual impression of paper boats drifting along on water. The boats were folded from sheets of failed math quizzes and tests. He not only recalls childhood memories in this work, but these drifting paper boats also reflects on how a child becomes unhinged because of bad grades. It is both a portrait of SHYU’s growth, and a journey of exile of an alternative life. It hints at the self healing and psychological fulfillment in an imperfect life.

In the introduction to his 2007 solo exhibition, SHYU explains that the “circle” was a basic principle that informs his work, as well as its metaphysical symbolism. He writes: “I create an opening at any point on this circle as a different visual expression within the operational mode. This opening also points to the limitlessness of creativity…” To put it another way, when a circle has an opening, it creates numerous creative opportunities and trajectories, and conversely, a complete circle is a closed loop onto itself, with its fate predestined. Incompletion is what gives opportunity for a man to find his own path, opening limitless possibilities. From the incomplete aspect of his life, SHYU Ruey-Shiann was able to forge his own completion. Although a complete and perfect circle never appears in his work, the viewer is always aware of his striving toward fulfillment.

At age 45, SHYU continues to recall memories of childhood and youth; and the re-presentation of youth remains an important theme in his work. Perhaps because of this, the child’s play in his work often reflects the social status quo of a Taiwan under authoritarian rule. “Collectiveness” is a common phenomenon in his early work. For instance, the flocks of migratory birds or fleets o paper boats described above, or the cluster of hermit crabs (seen in the 2000 work, One Kind of Behavior, a simulation of the tin water buckets ubiquitous in early elementary school classrooms), all reveal the collectivist tendencies prevalent in Taiwanese society in SHYU’s early childhood and youth. Even so, through SHYU’s filter, the bitter, oppressive atmosphere of institutional suppression during the era of the two Chiangs, all become a part of the simple innocence, joy and happiness of childhood. Faced with the gaps in life’s imperfect circle, he selectively uses memories of child’s play to embellish, to patch up, or even whitewash.

In 2012, SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s works in his solo exhibition at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM) continues in his original context of childhood memories. What has change is that he has began adding an element of projection in some of his work; for instance, in two recent works, Mom’s Drawer(2011) and The Edge of Memory (2012). The projected images within the mechanical installations can be directly interpreted as a projection of memory. In the work Mom’s Drawer, the mechanically controlled drawer holds old photos of mother; and the opening and closing drawer projects images that imitate the changing memory snapshots in the mind eye. In The Edge of Memory, there is no swing to sit on in the frame of the swing, but a digital projector simulates the shadow cast by a undulating swing, while sounds of children at play is broadcast. Though these two works similarly conjure memories, the introduction of projections is a direct announcement to the viewer of the fact that the subjects and objects of these memories are absent or no longer exist.

A similar scenario can be seen in Afternoon Rhapsody (2012). SHYU Ruey-Shiann creates a theatrical stage for a pair of primary school desk and chair. Mechanized chairs and tables dance a pas de deux. The desks and chair both have parts missing, again alluding to the unfulfilled childhood. However, just as with the drawer full of memories and the shadows of a swing, the lively dance between the desk and chair serve as a reminder that the child is long gone, leaving behind this phantom dance between the table and desk. Another large-scaled piece, Dreambox (2009-2012), begins by dismantling parts to a motorcycle rich with memories of youthful abandonment, and then reassembling all of the parts, toy-style, onto a life-sized model. The youth who once drove this Wolf 125 motorbike, SHYU Ruey-Shiann himself, is no longer the youth he once was. Without a doubt, the four large planks that hold the reassembled motorcycle parts have become a memory module, and the huge cube they comprise can ever only be a memory box for artistic display.

In comparison, the symbolism in the migratory birds and hermit crabs in SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s earlier work relied on simulating living objects, and successfully created a lifelike visual effect. Though paper boats were not living objects, the momentum of motion created an organic illusion. Through these simulated objects and scenarios, the artist successfully created a life force for the objects, and even an associated free will. In contrast, the new works in SHYU Ruey-Shiann’s TFAM Solo Exhibition Distant Rainbow belong unequivocally to memory and souvenir “objects”. Though these “objects” conjure memories of times past and enable associations of their collective role in the real world through SHYU’s unique organization and transformation, these “objects” corroborate their lifeless selves and experiences to the viewer, that they resemble a sudden flash of memory, an echo of history that reminds us that we are gradually growing old.

SHYU RUEY-SHIANN 徐瑞憲

SHYU RUEY-SHIANN 徐瑞憲